Conversation With a Ghost

A dialogue with Albert J. Nock on the Remnant and forming the Grey Robes

The Characters

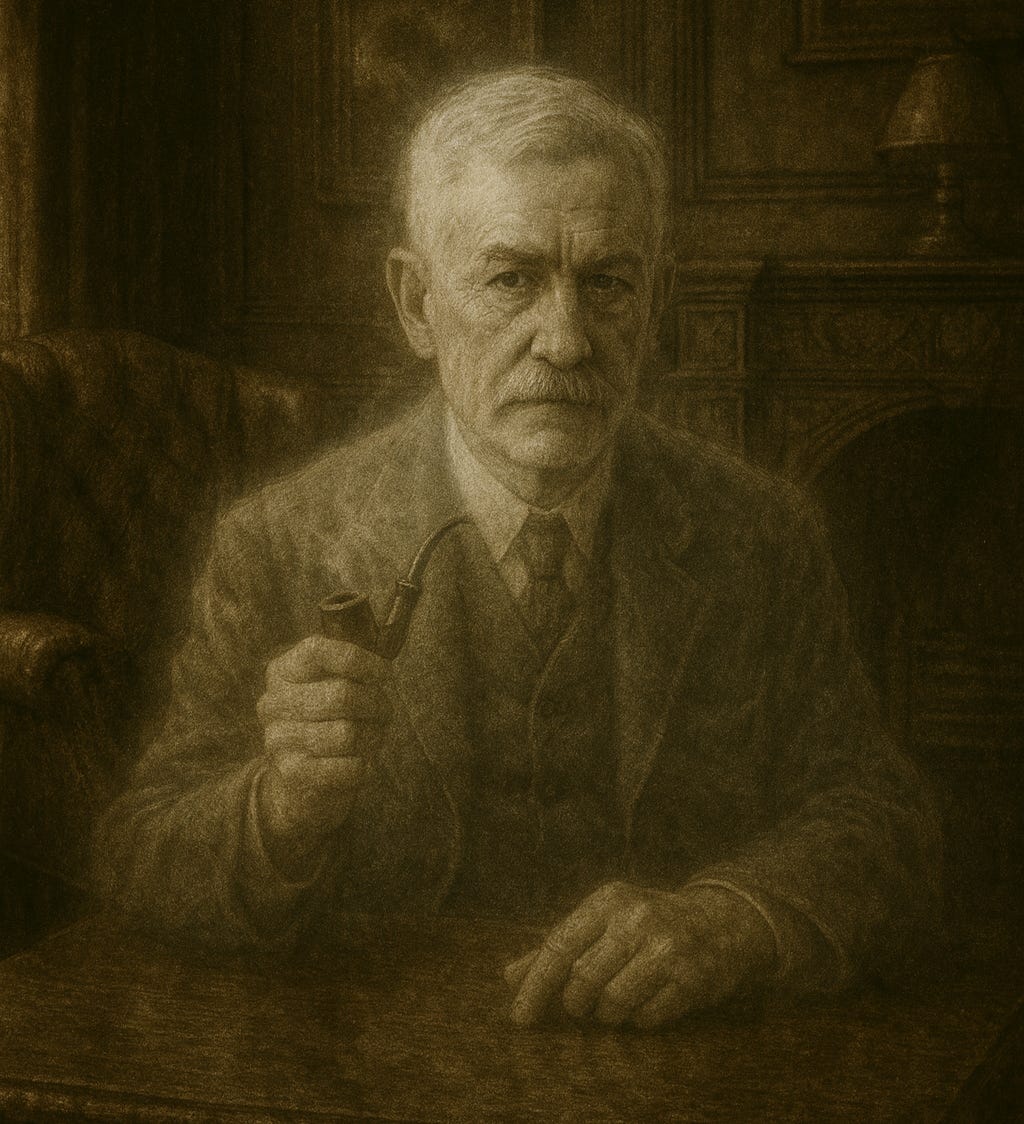

The Gentleman, as played by the Ghost of Albert J. Nock.

Me, as played by Max Borders

The Setting

A quiet drawing room corner, late evening. You have just finished explaining your vision for the Grey Robes—a siblinghood devoted to exploring Twelve Dimensions of human wisdom, mentoring select individuals, and working toward a consent-based polity. The learned gentleman, the ghost of Albert J. Nock, sits across from you, stroking his mustache thoughtfully.

The Gentleman: So you wish to found what you call the Grey Robes—a selective order that identifies and nurtures what the prophet Isaiah might have called the Remnant. Tell me, my friend, what makes you think such an enterprise would fare better than the countless missions to the masses that litter the ideological landscape?

Me: Well, that's why I'm drawn to your insights about Isaiah. You've persuaded me that the masses, by their very natures, cannot be the foundation for meaningful change. But the Remnant—those with both the head, heart, and will to appreciate our doctrine and the strength of character to live by it—they exist, right? They're just scattered. Disorganized. Waiting to be recruited.

The Gentleman: Ah, but there's where your optimism may be running out ahead of you. You speak of "recruiting" the Remnant, of being "selective." Do you recall what the Lord told Isaiah about the Remnant's most essential characteristic?

Me: You mean that they'll find him, not the other way around?

The Gentleman: Precisely. You cannot advertise for them, nor can you employ the usual schemes of publicity. The moment you begin actively recruiting, holding interviews, and establishing criteria, you risk falling into the very trap that ensnares those self-proclaimed prophets who are, in reality, herders for the credulous. The moment you try to manage the discovery of the Remnant, you've corrupted the enterprise.

Me: But surely some selectivity is necessary. I mean, if we threw open the doors to anyone, wouldn't we end up with the kind of people who are drawn to insipid things—the very opposite of the Remnant?

The Gentleman: You're starting to get it! Yes, indiscriminate openness would defeat your purpose entirely. But consider this: what if your "selection" process was not a matter of you choosing them, but of your work being so genuinely focused on truth, beauty, and uncompromisingly devoted to life wisdom that only those with the proper spiritual metabolism could digest it?

Me: You mean the substance is the filter?

The Gentleman: Exactly. Think about how Isaiah operated. He didn't water down his message to make it palatable. He didn't concern himself with whether his audience would find it convenient, or comfortable, or clear. He delivered the best he had, knowing that the Remnant would recognize it and the masses would overlook it. Your Grey Robes doctrine—including the Twelve Dimensions to be set out in the Codex—must be developed with this same integrity, mustn't it?

Me: Yes. But then, how can one ensure the work continues? How do I build something lasting if I can't actively identify or cultivate fellow travelers or successors?

The Gentleman: Ah, now you touch on something crucial. You speak of mentoring others through a "developmental path" so that they, in turn, can mentor others. But tell me—what makes you think the Remnant requires your particular developmental path? Might they not have their own unique relationship to wisdom?

Me: I... Well, yes, but I was thinking that even the brightest minds need structure, a framework for growth, particularly when they are young—when one’s height has not caught up with his feet, and his wisdom has not caught up with his talent. Besides, a framework brings people together through the seasons.

The Gentleman: But whose framework? Yours?

Me: Not exactly. I’m as much an assembler as a scribe. I borrow from the timeless. We stand on the shoulders of giants, as they say. And we stretch our yearning spirits into the realm of Unanswerable Questions, where, occasionally, we find new facets of the All, though never all of the All.

The Gentleman: How do you know all this isn’t just your own intellectual vanity and spiritual poverty dressed up as service to others? The masses love frameworks, after all. They like being told what steps to follow, what levels to achieve, and what insignia to earn.

Me: As do I, sometimes. I consider myself part of the Remnant. But, admittedly, I wouldn’t want to discard the discipline of structure or developmental stages. Indeed, I would be happy to accept some of your wisdom in the form of steps to follow or levels to reach—even if I, like a horn player, improvise the rest. My ear, keen for your wisdom, is an effort to do just that. Tradition and progress are commensurate. Design and freedom are reconcilable, as my friend Leif Smith says, of freeorder.

The Gentleman: Very well, then. Just be sure the Twelve Dimensions aren't just a more sophisticated version of what the masses crave, like a liturgical self-help book, because that will drive away the Remnant.

Me: That’s fair. But surely there's value in synthesizing wisdom, in creating trailheads for pathways others may explore if they wish. There is order in the fractal. There is value in orienting a siblinghood around a recognizable doctrine that overlays the weeks and months of the year. This way, we can honor helical time together. I expect that once I have managed somehow to attract other founding hierophants to the order, not to mention the first initiates, there will be feedback, revisions, and iteration cycles I could never have anticipated. We will always strive to strike a balance between rigid dogma and open-ended inquiry.

The Gentleman: Good. Indulging one’s own need to systematize or anticipate every question is folly. Let the developing doctrine be an ever-blooming expression of truth. Help others light their own paths, but never tell them where to go. That distinction is everything. The Remnant will sense the difference immediately.

Me: Between the desire to share knowledge and the longing to be acknowledged: How do I know which motivation is really driving me? Like anyone, I like the idea of being recognized as the founder of something meaningful. Who doesn’t? Still, my desire to leave meaningful traces outweighs any craving for recognition.

The Gentleman: Ponders a beat—Here's a test: are you more excited about the idea of people integrating the doctrine as is, or about the possibility that someone might take what you offer and develop it into something far beyond what you could have imagined? Are you building a monument to your own insights, or planting seeds whose full flowering you may never see?

Me: I’m glad you asked about the matter in this way. The other day, my friend James and I were talking. I said, “So you know, this isn’t for my self-aggrandizement. If I could know somehow that the seeds for the Grey Robes doctrine and order could be planted, then would take root, bud, and flower—but that my name would be entirely lost to history—I would still die fulfilled.” “Same here,” said James.

The Gentleman: Now we're getting somewhere. It suggests you might have something to offer. A dangerous prophet, or would-be cult leader, cannot see his own ego tangled up in his mission. (Ghostly lips pull at the stem of his ghostly pipe, and he exhales smoke more gossamer than smoke.) Now, tell me about this consent-based social order you mentioned. That certainly sounds like a mission for the masses.

Me: I don't think so. We’re not trying to convert the general public. We’re trying to liberate our progeny. If enough individuals build an Empire of the Mind—that is, if the Remnant can grow stronger and more connected around our shared commitments—then social change will flow organically in time. Or that is my hope.

The Gentleman: So you're not trying to reform the masses, but strengthen the foundation upon which they unknowingly depend. Like coral creatures building a reef, as I once put it.

Me: Yessir.

The Gentleman: Then here's a challenging question: what if the consent-based order you envision never comes to pass in your lifetime, or in your “siblings’” lifetimes? What if all your work amounts to is a small group of people living more wisely and perhaps more fully, but without achieving any significant societal-scale change?

Me: That is rather what I expect, to be honest.

The Gentleman: Then perhaps you are ready to serve the Remnant. Because serving the Remnant means working in “impenetrable darkness.” You cannot measure success by visible outcomes. The Remnant you nurture may not show the fruits of their work for generations. The ideas you plant may resurface in minds that never appreciate the origins. You must be content with excellence for its own sake.

Me: Still, I won’t be able to sustain that kind of work without feedback.

The Gentleman: Ah, but there is feedback—just not the kind that feeds the ego. When you encounter a mind that truly understands, that takes your offering and then transforms it into something luminous and new—there's no satisfaction quite like it. When you realize that an idea you shared has taken root in ways you never expected, in places you never foresaw, that's the compensation. That’s what Isaiah got out of it.

Me: So the Grey Robes must be content with this uncertainty—

The Gentleman: More than content. They must find it compelling, a feature of the mystery. That very uncertainty is what makes the work worthwhile. Anyone can preach to a predictable audience that responds in predictable ways. But to cast your bread upon the waters, never knowing where it will wash ashore or what will find sustenance in it—that's the adventure worthy of a first-rate mind.

Me: And the Twelve Dimensions I want to explore—ways to carve up the question, "How are we to live?"—do you think this question itself might be the organizing principle, rather than only my particular answers to it?

The Gentleman: Now you're thinking like a faithful servant of the Remnant! Yes, that question is what matters. Your particular formulations, your specific insights, your unique scars—these are offerings, not prescriptions. The moment you become attached to answers rather than devoted to the questions—to the question—you've lost the story that the All is meant to tell.

Me: Well, sir, I’m both inspired and terrified. If I can't actively recruit, can't measure my success, and can't even be certain my approach is valuable—how do I begin?

The Gentleman: Have faith. Renounce the destination in favor of the journey. Begin by doing the work that needs doing—work that springs from your sublime encounter with glimmers of truth rather than from any ambition to influence. Develop your Codex not because you want a flock, but because the ever-lingering question demands it. You must write, speak, and create not to build an order per se, but because failing to express what you've discovered would be to betray the gift.

Me: And then?

The Gentleman: Then you wait. Continue the work. Remain available. And trust that if there's anything to what you're doing, the Remnant will find you. They'll recognize something, take what serves them, and carry it forward in ways you may not be able to predict or control.

Me: Sounds lonely.

The Gentleman: It can be. But remember what Elijah discovered… 7,000 he never knew about. The Remnant is always larger and more active than any individual can perceive. Your work becomes part of a vast, invisible network of authentic effort. You may never see the connections. But trust they exist.

Me: And if I'm wrong? If I'm just another scribe making hatch marks on tablets lost to time?

The Gentleman: The Remnant will ignore you, and you will have engaged in spiritual self-gratification until you die. However, if you serve even a few unseen others, rather than your ego, and if your work has substance and your motivation is giving to posterity, then the rest is irrelevant. Your work will find its place in the patterns of the unfolding All.

Me: So the Grey Robes might transform into something I never imagined?

The Gentleman: Yes.

Me: Or it could be lost, like Qoheleth’s lush vineyards, his youthful pleasures, and his old-age wisdom—with all being vanity and futility.

The Gentleman: Or, you could say, “To everything there is a season.” It might disappear entirely, having served its purpose before the heat death of the universe. The question is not whether your vision is realized, but whether you can commit to excellence and inquiry for their own sake, trusting that such commitment will serve whatever purposes the unfolding All has in store for you and yours.

You: I’m feeling uncertain again.

The Gentleman: Good! If you didn’t, we'd be wasting our breath. Now do the work that calls you. Forget about recognition and influence. Do the work because something in you demands it. If there's anything worth finding, the Remnant will come.

The gentleman rises, gathering his papers.

The Gentleman: Oh, one final thought… If the Remnant does find you, don't try to hold onto them. Let them take what serves and leave what doesn't. Don’t forget, your job is to offer the best you have, not to find a faithful flock. The moment you prefer loyalty to liminality, you've extinguished any fire that might ignite their wicks. And you’d better believe, whatever this is, right now, is but a candle in a windstorm.

Me: Thank you. I have much left to do.

The Gentleman: smiling—Good evening, my friend.

He walks away, then floats away, then disappears, leaving me in impenetrable darkness.

I took this concept from Albert J. Nock. His essay, Isaiah’s Job, first appeared in The Atlantic Monthly in 1936. Nock was the founding editor of The Freeman print magazine. Ironically, I was the editor when the magazine’s controlling board decided to close it in 2016. Thanks to the newest Grey Robe and member of the remnant, James Harrigan, for the inspiration. Turns out the Gentleman isn’t wrong.

Never heard of nock before. Thanks for the exposure

You are not alone.